Who Was Dr Alain Locke and What Were His Views About African American Art

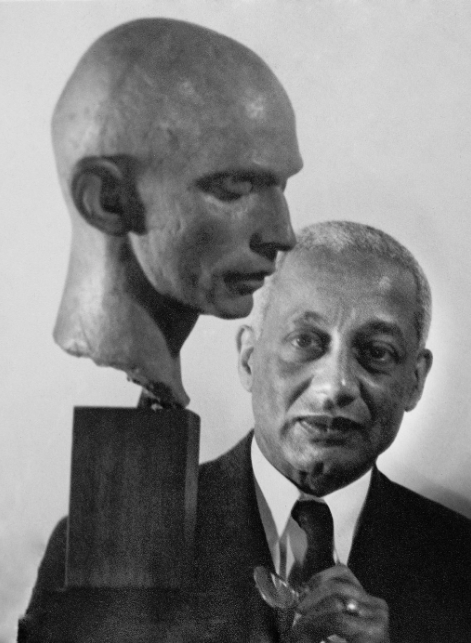

Photograph taken past Gordon Parks/The Gordon Parks Foundation

Alain Locke was born September thirteen, 1885 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania to Pliny Ismael Locke and Mary Hawkins Locke. Pliny Locke obtained a police degree from Howard University and worked as a mail clerk in Philadelphia, while Mary Hawkins Locke worked as a teacher. The Locke's were engaged for 16 years and only had one child, Alain. When Alain Locke was six years old, his begetter died, forcing his female parent to financially support him through teaching. At some point in his babyhood, Alain Locke contracted rheumatic fever, permanently damaging his middle and restricting his physical abilities. Consequently, Locke spent much of his babyhood reading and playing both the piano and violin.

A 1949 note written by Locke revealed both his reflection and struggles with the intersectionality of his identity: "Had I been born in ancient Greece, I would accept escaped the kickoff [his sexual identity]; in Europe, I would take been spared the second [U.S. racial segregation policies and discrimination]; in Japan I would accept been in a higher place rather than below average [tiptop]."

In his short life, Locke made several notable accomplishments. One of Locke'south about notable accomplishments was that he became the first African-American and openly gay homo to be awarded a Rhodes scholarship to Oxford University. Furthermore, Locke is credited as ane of the "originators" of the Harlem Renaissance and New Negro movement. Locke contributed to both movements by: promoting and emphasizing values, diverseness, and race relations; and encouraging and challenging African-Americans to place, appreciate, and embrace their cultural heritage–along with the traditions of other cultural groups–while simultaneously making the endeavour to integrate into the larger society.

Locke was clearly well-educated, which established a foundation for his career and his role in both the Harlem Renaissance and the New Negro movement. From 1904 to 1907, Locke attended Harvard University, completing a 4-yr philosophy degree in only three years and graduating magna cum laude. While at Harvard Academy, Locke was elected to Phi Beta Kappa, a highly distinguished honor society, and won the Bowdoin Prize. Locke and then attended Oxford University from 1907 to 1910, where he received another undergraduate degree in literature. Locke was the first African-American Rhodes Scholar. The adjacent African-American Rhodes Scholars were not until 1963, when John Edgar Wideman and John Stanley Sanders were selected. While it is uncertain if the 1907 selection committee members knew that Locke was African-American when they selected him as a scholar [although evidence has been discovered that they may have known], it is certain that some of Locke's fellow American colleagues were non "ready to share the pedestal with a black human being" and refused to alive in the aforementioned Oxford college. In 1911, Locke attended the University of Berlin in Federal republic of germany. Nigh a twelvemonth afterward, Locke became an Assistant Professor at Howard Academy in Washington, DC. Locke later returned to Harvard University in 1916, where ultimately earned a PhD in Philosophy in 1918, before he rejoined the faculty as a full-time Philosophy professor at Howard University. In 1921, Locke became the chair of the Philosophy department at Howard Academy and remained in that position until he retired in 1953. Upon his retirement, Locke was awarded an honorary doctorate from Howard University. Throughout his academic career, Locke closely studied African civilisation and traced its influences on western culture. Primarily through his career and efforts in vocalizing his ideas near the role of African-Americans in American order, Locke established close relationships to Langston Hughes, Countee Cullen, Jean Toomer, Rudolph Fisher, and Zora Neale Hurston. Furthermore, Locke is said to accept inspired Martin Luther King Jr., who considered Locke to be an "intellectual leader on par with Plato and Aristotle."

Throughout his career, Locke made pregnant contributions to the field of philosophy. Locke emphasized the necessity of depending on and determining values to aid guide human conduct and interrelationships. Furthermore, Locke praised the idea of respecting the uniqueness of each personality in a society because he believed that this respect would allow personalities and society to fully develop and remain unique within a democratic ethos. Locke as well argued that race is a fabrication and that civilisation created visions and interpretations of race. This was a shocking statement to make during a time when he—and other African-Americans—faced segregation and discrimination daily. Locke is considered one of the founders of pragmatism. However, pragmatists did non include him in their history considering they believed that his ideas were a reflection solely of African-Americans.

Locke familiarized American readers with ideas and key people in the Harlem Renaissance and New Negro motion. For instance, Locke edited a special issue for Survey Graphic in March 1925, which expanded into the New Negro, an anthology of fiction, poetry, drama, and essays. Additionally, Locke edited the "Bronze Booklet" studies of cultural achievements by African-Americans, annually reviewed literature by and most African-Americans in Opportunity and Phylon, and often wrote about notable African-Americans for the Britannica Book of the Year. Locke's published works include: 4 Negro Poets (1927), Frederick Douglass, a Biography of Anti-slavery (1939), Negro Art: Past and Present (1936), and The Negro and His Music (1936). Before his untimely death, Locke was working on a manuscript for a definitive report on the contributions of African-Americans on American civilisation. While this manuscript was left unfinished, information technology formed the basis for Margaret Just Butcher's The Negro in American Culture (1956).

Locke encouraged African-American painters, sculptors, musicians, and other artists to apply African sources for inspiration in their work. Specifically, Locke encouraged artists to reference African sources to improve understand African and African-American identity and discover African-based materials and techniques to create and limited different art forms. In literature, Locke pressed African-American authors and writers to explore subjects in African and African-American life and to set loftier artistic standards for themselves. Additionally, Locke was an early advocate for recognizing the importance of African-American slave songs and spirituals to meliorate sympathise America's musical history. Locke claimed that "the very element that make them [slave songs and spirituals] spiritually expressive of the Negro make them, at the same time, deeply representative of the soil that produced them…They vest to a common heritage."

Locke died on June 9, 1954 in New York City at the historic period of 68.

After his death, Locke was cremated and his ashes were given to his close friend and executor, Philadelphia activist and educator Arthur Huff Fauset. When Fauset died in 1983, his niece, Conchita Porter Morrison, contacted Rev. Sadie Mitchell to human action every bit an intermediary betwixt Morrison and Howard University.

In the mid-1990s, J Weldon Norris, Howard Academy'due south coordinator of music history, was visiting St. Thomas Church for a concert when Rev. Mitchell approached Norris, asking to requite him Locke'due south cremains to accept back with him to Howard University.

Locke's papers are housed in several greyness archival boxes at Howard Academy'due south Moorland-Springarn Enquiry Middle. Locke's cremains were also stored within a brown paper bag in the enquiry center. The paper purse was inscribed with "Cremains given to Locke's friend Dr. Arthur Huff Fauset. Arthur is deceased. I kept the remains to give to Howard. —The Rev. Sadie Mitchell, Associate of St. Thomas Church." In 2007, the cremains were transferred to Howard University's West. Montague Cobb Research Laboratory in 2007. This lab also housed the remains from New York's African Burying Basis along with 699 [more often than not] African-American skeletons. Mack Mack, the director of the lab, ensured that the cremains were repackaged in a simple urn. Locke's remains and so stayed in the urn at the lab until jump 2014.

60 years after his death, Locke was finally given a permanent resting place at Congressional Cemetery (Range 62, Site xc). The funds for Locke'due south inurnment and memorial service were planned and funded by African-American Rhodes Scholars. Locke'southward plot location is very plumbing equipment—his plot is adjacent to the first director of the Smithsonian's National Museum of African Fine art, Warren Robbins. Locke was not buried with his mother at the Columbian Harmony Cemetery because the cemetery is now a metro station. In circa 1959, 37,000 graves from the Columbian Harmony Cemetery were transferred to Landover, but these graves were left unmarked.

Locke's black granite gravestone is inscribed with four symbols on the western elevation. The symbols are: a 9-pointed Baha'i star; a Zimbabwe bird, representing the African country formerly chosen Rhodesia, which the American Rhodes community adopted; a lambda, representing gay rights; and the Phi Beta Sigma symbol. A simplified reproduction of a bookplate created by Harlem Renaissance painter Aaron Douglas sits at the center of the stone. The keepsake portrays a dramatic art-deco depiction of an African adult female'due south face up set against a sunburst. The words "Teneo te, Africa" translate to "I hold you, my Africa."

Works Cited:

"Alain Locke Biography." Encyclopedia of World Biography. Accessed January 16, 2019. https://www.notablebiographies.com/Ki-Lo/Locke-Alain.html.

Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. "Alain Locke." Encyclopædia Britannica. September 09, 2018. Accessed January 16, 2019. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Alain-LeRoy-Locke.

Emanuel, Gabrielle. "Alain Locke, Whose Ashes Were Found In University Archives, Is Buried." NPR. September 15, 2014. Accessed January 16, 2019. https://world wide web.npr.org/sections/codeswitch/2014/09/15/347132309/alain-locke-whose-ashes-were-plant-in-university-archives-is-cached.

Haslett, Tobi. "The Man Who Led the Harlem Renaissance-and His Hidden Hungers." The New Yorker. May 31, 2018. Accessed January 16, 2019. https://world wide web.newyorker.com/mag/2018/05/21/the-man-who-led-the-harlem-renaissance-and-his-subconscious-hungers

Comments are closed.

Source: https://congressionalcemetery.org/2019/01/17/alain-leroy-locke-1886-1954/

0 Response to "Who Was Dr Alain Locke and What Were His Views About African American Art"

Post a Comment